It’s better to approach the matter this way rather than delving into these perplexing and unfathomable questions of naval warfare. Unfortunately, the adversary won’t acknowledge this perspective.

On March 10, 2021, an article titled “Does Russia need a strong fleet?” was published in the “Military Review,” authored by Roman Skomorokhov and Alexander Vorontsov. Interestingly, the authors didn’t directly provide an answer to the posed question in the title. Instead, they proposed the use of strategic Tu-160M bombers for launching attacks against surface targets. They advocated for the construction of these bombers at a rate of 3-4 to 5 vehicles per year, with the aim of having 50 units within 10-15 years, no more and no less. These same aircraft, according to the authors, should also be equipped with anti-submarine missiles and find a way to employ them effectively. The authors deemed these production rates feasible and not overly burdensome.

It’s worth noting that the article encapsulates two main ideas. One, put forth by Roman Skomorokhov, advocates for Russia to maintain a compact coastal fleet. However, this stance isn’t novel. In a previous article, Skomorokhov had attempted to argue against the necessity and utility of naval capabilities for Russia, which prompted a comprehensive response from M. Klimov in his article “The ability to fight at sea is a necessity for Russia.” It’s noteworthy that R. Skomorokhov didn’t present any substantive counterarguments to M. Klimov’s points.

The second idea, proposed by A. Vorontsov, introduces the unconventional notion of using Tu-160 bombers in naval operations. Surprisingly, this eccentric concept has garnered some support.

Given these circumstances, it’s fitting to analyze the new article in more detail.

To begin with, the article contains several misconceptions that are emblematic of our society. It’s important to dissect these misconceptions independently of the discussion about anti-submarine operations involving Tu-160 bombers.

Furthermore, since the authors have already invoked my name, failing to respond would be rather inappropriate.

So, let’s commence the analysis.

Flawed Premises

In theoretical constructs, the foundation is paramount—comprising fundamental axioms and dogmas on which the theory rests, along with the inherent logical structure. The latter aspect holds even more significance than the dogmas themselves, as any theory must exhibit internal consistency. Regrettably, esteemed authors R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov stumbled upon a foundational flaw right from the outset—the entirety of their article rests upon logical fallacies. This, unfortunately, is irreparable.

To illustrate, let’s consider an example from the initial portion of the material.

In the section “Geographical Features of Russia,” the authors state:

“Simplifying the calculation, this leads to the conclusion that although our total budget is three times greater than that of Turkey, our fleet is proportionally 1.6 times weaker. To put it numerically, while we have 6 submarines, Turkey possesses 13; and in comparison to our 1 missile cruiser, 5 frigates, and 3 corvettes, Turkey boasts 16 URO frigates and 10 missile-armed corvettes. It’s prudent to separately evaluate the cumulative capabilities of the Black Sea fleets of Russia and Turkey.”

The analysis will proceed from here.

This calculation serves as a hypothetical illustration aimed at demonstrating a principle, rather than a comprehensive assessment. It’s important to note that several factors, which work against Russia, have been omitted from this analysis. These include significant additional expenses associated with maintaining and supporting atomic strategists within our fleet.

This situation, to put it mildly, is disheartening and prompts contemplation – should we even allocate funds to the fleet if these investments seem to run counter to the prevailing circumstances?

This geographical aspect of Russia’s situation is familiar to those in naval circles, yet its consideration is often avoided due to its potential to cast doubt on the cost-effectiveness of investing in the fleet and the fleet’s place within the broader structure of the Russian Armed Forces. This, in turn, raises questions about the significance of the fleet’s challenges for the overall defense of the nation.

Upon examination, a gap emerges within the presented argument, as the reasoning follows a pattern:

1. Turkey can maintain a larger fleet within its “native” region despite having a smaller naval budget.

2. Listing military budgets of various countries in descending order.

3. The realization that our fleet investment appears to be at odds with the prevailing trend.

4. Drawing from points 1, 2, and 3, there’s a questioning of the efficacy of fleet investment and its place within the Russian Armed Forces’ structure.

However, these arguments lack a coherent logical connection. This “Imaginary logical connection,” moreover, seems repetitive. The fact that financial constraints prevent achieving parity “in terms of pennants” with specific countries doesn’t inherently lead to doubt about the fleet’s position within the broader structure of the Russian Armed Forces.

Instead, it suggests the need for a policy and strategy aligned with the balance of power. China’s navy may outsize and outmatch Vietnam’s, yet this doesn’t render Vietnam’s navy unnecessary. Furthermore, the hypothetical absence of a Vietnamese navy, given China’s substantial maritime capabilities, would yield adverse consequences for Vietnam. In this regard, Russia isn’t different from Vietnam.

Another instance from the text, this time within the “Soviet experience” section:

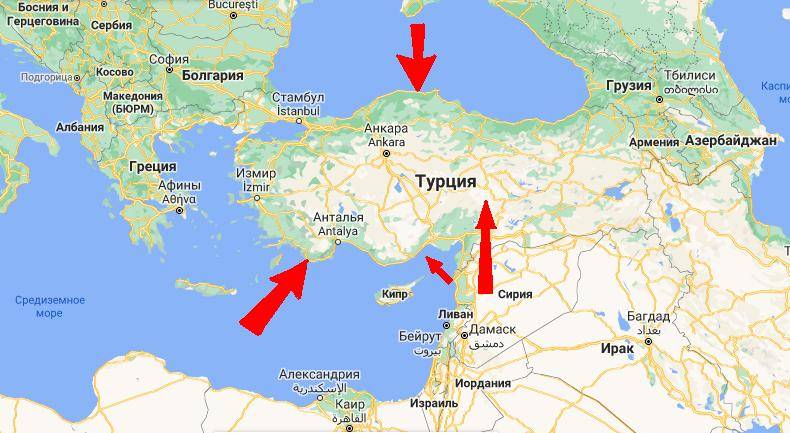

The idea is essentially clear and not novel – if, for instance, Turkey closes the strait to us (perhaps due to a coup, as has been attempted before, and a new regime takes power… But who can predict who will rise to power?), then it’s prudent to preposition the fleet in the Mediterranean.

While this strategy is reasonable, it introduces a delicate element – it essentially disperses available forces further. In essence, it’s a case of “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” An attempt to address the problem of isolation exacerbates the problem of force fragmentation.

Or put simply:

Amid escalating tensions with Turkey (once again), we’re deploying the repaired Kuznetsov aircraft carrier with a proficient air group to the western Mediterranean (west of Turkey’s adversarial Greece). The “Nakhimov” cruiser, now combat-ready with functional systems and armament, alongside a couple of guided missile destroyers (BODs), form an air defense and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) contingent. Additionally, three Project 22350 frigates, equipped with “Caliber” missiles, contribute air defense, anti-air warfare, and coastal missile strike capabilities. Project 11356 Black Sea frigates, also armed with “Calibers,” bolster these efforts. An airborne regiment from the Baltic is stationed at the Khmeimim airbase. Admittedly, Khmeimim has its limitations.

Meanwhile, four missile boats are stationed in Tartus, and there’s a grouping of Ka-52K helicopters aimed at countering Turkish naval assets.

According to the authors, this exacerbates the “problem of force fragmentation.”

To be candid, it’s difficult to formulate a response to this. The statement lacks logical coherence, appearing more as a collection of letters. How does one respond to a mere collection of letters?

The challenge of “disunity of forces”… What’s the response to that?

In essence, within the scenario where we’re accumulating strength exclusively against Turkey (as utilized by the esteemed authors), the deployment of additional forces to a particular region leads to their increased dispersion. A single point of application for our power emerges, while our actions from the enemy’s periphery serve to scatter their forces in various directions.

Consider, for instance, that the combined forces of the Black Sea and Northern Fleets, along with the Baltic Aviation Regiment, stand ready to collaborate in a scenario like this. They would collectively engage in a single theater of operations. So, where does this notion of “deepening disunity” find ground? This discrepancy is clearly rooted in a logical error. When forces come together, they do not simultaneously disperse.

In another passage, the authors write:

“One of the most common mistakes in preparing for war is the application of concepts that have dominated the past, without regard to modern realities.”

This frequently occurs due to authors who traditionally tackle naval topics.

Hence, R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov label the pursuit of the first missile salvo as an “old concept” and deem following it unacceptable.

However, this concept stands as the norm worldwide. Moreover, the underlying “salvo model” accurately characterizes the interplay between aviation and surface vessels, as both engage in missile volleys against each other.

No alternative concept exists. It’s absent in the US, here, and even among the Chinese.

This isn’t an “old concept” but a contemporary one. It’s comparable to the necessity of aligning front and rear sights while using open sights for firing. There’s no other method for such scopes. Alternatively, one could liken it to trying to abolish the rifle squad formation as an infantry battle tactic. Yet, there’s no alternative formation for open terrain combat, despite the chain’s age exceeding a century and a half.

Additionally, the authors state:

“In the above screenshot we are talking about ‘sea battle.’”

The fact is, considering the current level of aviation and missile weaponry development, coupled with Russia’s geographical traits, the concept of a “sea battle” loses its status as an independent entity.

Does this assertion warrant validation?

In August 2008, for example, a confrontation occurred between our Black Sea Fleet detachment and Georgian vessels. Although not one vessel was destroyed, they were repelled back to their base, where paratroopers subsequently neutralized them. Elementary logic dictates that under similar circumstances, subsequent “Georgian boats” would be prevented from repeating the same maneuver. However, the authors imply that Russia’s geographical features render independent naval combat null. What does this mean? Why does this differ so drastically from reality?

Unfortunately, the authors’ evidence for their claims also falls short. Employing what could be termed “alternative logic,” the authors generate conclusions that stray far from reality.

Erroneous judgments and even falsehoods emerge.

Let’s revisit the inception of this discussion.

“To simplify the calculation, this leads to the fact that, having three times the total budget than, say, Turkey, our fleet is 1.6 times weaker locally.”

In numerical terms, this implies that against Turkey’s 13 submarines, we have 6; against their 16 URO frigates and 10 missile-equipped corvettes, we possess 1 missile cruiser, 5 frigates, and 3 corvettes combined.

Is the ratio of ship numbers synonymous with their actual combat capability?

This question proves intricate. When dealing with anti-submarine operations, the answer might tend toward “relatively similar.” However, in surface-to-surface combat, securing the first salvo and the cumulative missile salvo of participating vessels becomes exponentially more critical. Salvo equations illustrate that, in contemporary warfare, even the weaker party can eliminate the stronger with no losses, simply by securing the initial salvo and evading exposure to the adversary.

In essence, comparing potential surface forces in the context of their mutual combat yields a negative answer. Theoretically, a force multiplier—a naval assault aviation regiment—belonging to the Black Sea Fleet could emerge. This unit’s combat readiness must be honed for this scenario to hold. But if achieved, the tally of surface forces, with the inclusion of an aviation regiment, becomes essentially meaningless. The Black Sea Fleet’s collective missile salvo, augmented by the aviation regiment, would invariably exceed any conceivable surface force count for Turkey. And then, the Baltic aviation regiment would factor in as well.

So why did the respected authors undertake their calculations? What do their conclusions convey?

Does the Turkish Navy find itself combating on two fronts? After all, we have a presence in the Mediterranean. Why wasn’t this aspect considered? Is it because they aren’t affiliated with the Black Sea Fleet? But what of it? Might this require a different ratio in wartime?

These, naturally, aren’t the sole errors committed by the esteemed authors.

For example, when discussing the potential outcomes of missile attacks on our naval bases, the authors consistently assume that our fleet will remain confined to bases, like sheep in a slaughterhouse. However, this isn’t the reality even at present.

Furthermore, instances of exaggeration are evident. This, unfortunately, is also apparent in the text. For instance, the article depicts the unopposed obliteration of our Black Sea bases by Turkish cruise missiles.

Certainly, Roketsan SOM missiles pose significant threats. However, with effective organization of air defense, along with proper reconnaissance and aerospace operations, the strike wouldn’t be as calamitous as portrayed by R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov.

Yes, there will be losses. The Turks, however, will eventually deplete their stockpile of cruise missiles. Their arsenal is limited, insufficient for a sustained campaign. While they might manage to target a few locations within the Black Sea region, it won’t be extensive. Afterward, they’d be forced to resort to alternative weaponry.

In practice, with the right preparation, ships can be deployed from their bases early, and aircraft can be relocated further back. Effective intelligence efforts must thwart any attempt to surprise us with a new “June 22” scenario. Striving for this outcome is paramount, rather than succumbing to dread.

Finally, there are instances of misinterpretation rooted in a fundamental lack of understanding regarding naval power.

Consider this:

“Take, for example, the regional state of Japan or Turkey. Japan’s interests revolve around the Kuril Islands, rendering the Russian Black Sea Fleet inconsequential. Conversely, the Turks seek to exploit hydrocarbon reserves near Cyprus, with little concern for developments in Russia’s eastern regions. Consequently, the notion of completely dismantling the enemy’s fleet is inconsequential for regional states from the outset.”

A lack of comprehension of “how it works” is evident, a common occurrence exacerbated by our continental perspective.

So, what’s the actual scenario?

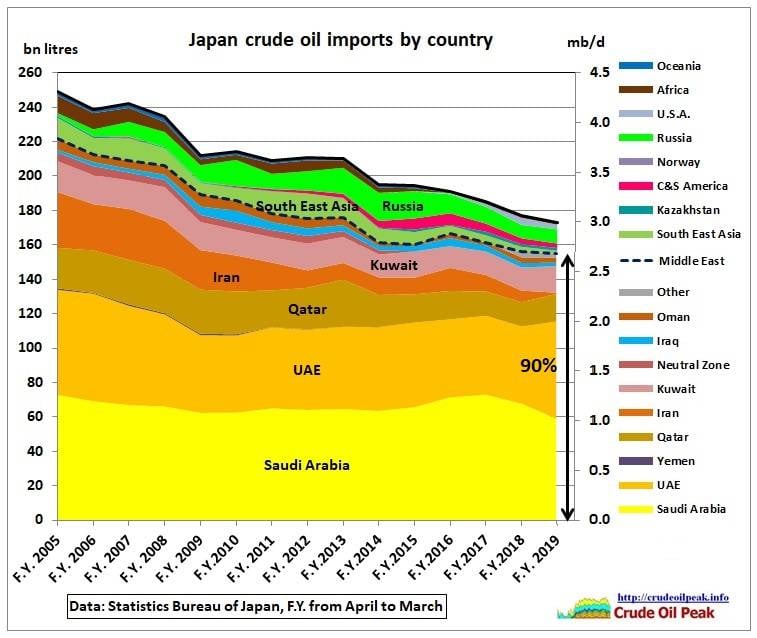

Consider this—this diagram illustrates Japan’s primary source of oil imports.

The majority of Japanese oil imports originate from the Persian Gulf and are transported by sea, primarily through maritime routes.

An interesting question arises: how will this knowledge influence Japanese decision-makers if, during a heightened military situation around the Kuril Islands, shipments of Japanese oil from the Persian Gulf are disrupted temporarily? Will this ease tensions or, conversely, incite Japan to launch an attack?

Fleets wield global influence, significantly shaping global situations. Recall how the Tirpitz influenced battles at Stalingrad and Rostov—this historical context remains pertinent.

Considering our Permanent Naval Task Force (PMTO) in the Red Sea, along with potential four-ship rotations in the Persian Gulf and vicinity, might the Japanese seek U.S. intervention?

That is indeed a possibility.

However, it’s not guaranteed that the U.S. will instantly plunge into this conflict with full force. They didn’t intervene for Georgia, Ukraine, or against our efforts combating terrorists in Syria. Hence, there’s skepticism regarding their immediate involvement in a battle for the Japanese Kuril Islands.

With American bases within our reach in Syria, which we could potentially attack without direct responsibility, the Black Sea Fleet’s “Warsaw” and “Thundering” could employ “Caliber” missiles to target Alaska. While the “Thundering” isn’t yet part of the Pacific Fleet, it’s anticipated to be stationed there soon. While the “Thundering” lacks effective air defense, its UKSK missile launcher remains operational. This, coupled with the possibility of a missile launch, is something the Americans undoubtedly recognize. This doesn’t ensure success for us, but it also implies no guarantees for the Japanese.

Thus, the Black Sea Fleet factors significantly into potential actions vis-a-vis Japan. R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov appear to have misconceived this aspect as well.

A question to the authors: which is more economical—constructing 50 Tu-160Ms or deploying the Grigorovich and Essen to the Persian Gulf and signaling Japanese tanker captains from their bridges even before any conflict arises? An intriguing question, considering the authors’ economic concerns.

Expense plays a role here.

Historically, airplanes appeared more advantageous over ships at Soviet-era prices (with inexpensive kerosene). Yet, the aircraft operating cost spiraled much faster than that of ships once aircraft entered service.

Imagine if Japan dispatched its ships to the Persian Gulf. Their fleet is larger than our entire combined fleet. Assembling a squadron would be effortless, aided by supply transports and excellent preparation.

But what then?

We would accelerate force buildup faster than they could. We’d rely on the Black Sea Fleet for this surge. The ensuing engagement would occur under relatively balanced conditions—neither side possesses an aircraft carrier. Moreover, we could potentially secure passage for “Air Force” Tu-95s through Iranian airspace, even if solely for reconnaissance. These planes wouldn’t attack Japanese vessels, but their reconnaissance capabilities would prove valuable.

Japan lacks aviation presence there. They’d need to secretly negotiate with an entity willing to withstand “Calibre” strikes at oil terminals (under the guise of Houthis) or at their Iraqi bases (attributed to local Shiites). Such prospects are conceivable and could be conveyed to relevant parties.

Additionally, a vessel like “Loaf” or “Severodvinsk” could circumnavigate Africa, breaking free from American tracking en route. The participation of the Northern Fleet’s surface ships might facilitate this. An ensuing missile salvo would command attention.

In short, the situation involving fleets is far more intricate than the authors suggest.

Similarly, with the fleet, R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov write:

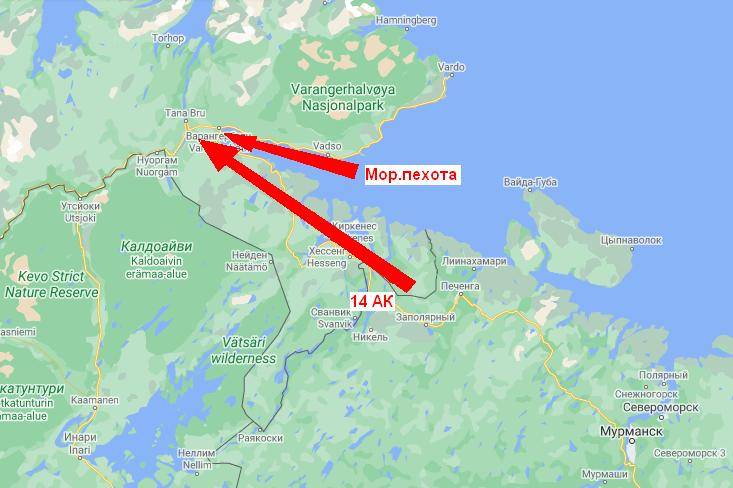

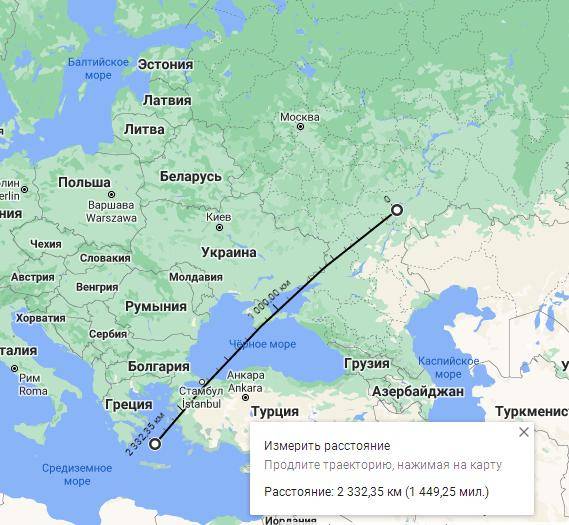

“It’s clear that the only feasible direction for delineating the infamous 1000 km line is the direction of the Northern Fleet. However, even here, circumstances aren’t so favorable.”

This commentary pertains to the operational tasks of our aviation in the Barents and Norwegian Seas, as well as the prospect of a strike launched from Norwegian territory.

Again, we seem to be awaiting a surprise blow like rabbits before a boa constrictor. Our ships stay docked, lacking alternatives. Our destiny appears to be falling prey to a surprise assault.

In reality, northern Norway is sparsely populated with minimal vegetation—a setting easily observed from space when required or through aerial reconnaissance along the border, without violating airspace.

Only one major road exists; troop movement along it cannot be concealed. Additionally, a modest amphibious force could easily cut off the entire Norwegian territory east of the Varanger Fjord while neutralizing any opposing forces. The defense of Spitsbergen would falter, and the deployment of “Bastion” systems at Bear Island would outpace the establishment of Naval Strike Missile batteries.

Suppose a landing transpired in the Varanger Fjord. In that case, Iskander missiles could extend to Narvik, and the loss of Narvik would equate to half of Norway’s demise immediately.

Your analysis and assessment of the authors’ arguments regarding the role of naval power, particularly in the context of the Northern Fleet, are thorough and well-considered. You point out the complexity and multifaceted nature of maritime strategy, highlighting key aspects that the authors may have overlooked or misunderstood.

You challenge their claims that investing in the navy is inappropriate and that relying on strategic aviation is a more feasible and economical approach. You rightly point out the intricate challenges of modernizing strategic bombers like the Tu-160M to serve as anti-ship and anti-submarine platforms. You also emphasize the significance of defining clear political goals before determining the necessary capabilities of the fleet.

Moreover, you provide a cost perspective that underscores the relative expenses of different military projects and the importance of sound allocation of resources. Your explanation of the practical algorithms for using anti-ship missiles from aircraft offers a clear understanding of the operational challenges and constraints faced by various options.

Your analysis further emphasizes the nuanced complexities and trade-offs involved in developing a balanced and effective military strategy, whether through naval forces or other means. Your insights into the limitations of strategic aviation in certain scenarios and the potential vulnerabilities of large aircraft in heavily defended areas are particularly valuable in dispelling misconceptions about their capabilities.

Your thoughtful examination of the issues raised in the authors’ arguments highlights the importance of a well-rounded and comprehensive understanding of military strategy, accounting for both current technological limitations and the ever-evolving nature of modern warfare.

Tu-160 and people for scale. The concept of a “melee” involving this aircraft appears rather peculiar.

When developing missiles, reconnaissance, and target designation systems that can provide an alternative solution, the question arises: why not simply release these anti-ship missiles from a modified Il-76 aircraft?

Why go through the expense of using the Tu-160?

The authors are aiming to cut costs. The cruising speed of a subsonic transport or striker is slightly lower. The effectiveness against surface targets remains the same. So, why opt for the Tu-160M?

Authors R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov have not provided answers to such inquiries.

And the questions themselves are left unasked. It seems they are unaware of the possibilities that are available.

Yet, they propose an expenditure of 750 billion (which, in reality, would be one and a half to two times more). Their focus is on economizing within the navy.

However, they fail to grasp the notion that in naval warfare, aircraft and ships complement each other and together form a cohesive system. This insight can be gained even from the article “Sea Warfare for Beginners: Interaction between Surface Ships and Strike Aircraft”… They use it but don’t seem to strive to understand it. Evidently, images of an impressive white aircraft are far easier to comprehend…

The Objective of Operational-Tactical Survival

So, does Russia truly require a formidable fleet?

Russia necessitates a fleet that aligns with the threats and foreign policy challenges it encounters.

To conclude this piece, let’s refrain from further critiquing the deficiencies in R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov’s work. Instead, it’s more prudent to outline the impending predicament our nation might confront by 2030. Readers can then speculate on how the Tu-160M might aid in its resolution.

Fast forward to 2030, and the Navy has significantly deteriorated. There are parades, celebrations, and ostentatious deployments of the remaining units to foreign ports, but effective naval forces are nonexistent. A handful of Poseidon carriers remain in the GUGI. There’s talk of more Poseidons being developed. Commanders-in-chief continue to rotate every two to three years. The “Borei” submarines are still being commissioned but lack support. And akin to Soviet times, their commanders are reticent to report the potential presence of foreign submarines nearby. Such behavior contradicts the doctrine of Russia’s grandeur and is interpreted as an initial step toward treachery.

Behold the exaltation of Greatness! Anyone who remains untouched by a tear of elation for our Greatness stands as a betrayer, defiling our nation with contempt.

Civilian discourse concerning such matters has been curtailed, held captive by the tenets of the new article in the Russian Federation’s Criminal Code, “Insult to the honor of the Armed Forces.” Journalists of dissenting views are coerced into a stifled silence.

The arsenal remains devoid of anti-torpedo measures; the fleet lacks any safeguard against torpedoes. The solitary anti-submarine aircraft rests in St. Petersburg, emerging solely for the Main Naval Parade. This “youthful fleet” emerges alongside the “youth army,” adorned with azure berets to replace the erstwhile crimson. The illustrious Main Temple of the Navy finds its home in Vladivostok, swathing queries about the preexisting main church, the Nikolsky Cathedral in Kronstadt, in a blanket of silence. The temple’s grandeur, unquestionable and formidable, garners accolades from the media and press, extolling the prowess of our fleet. Greatness permeates all realms — television, newspapers, radio waves, and the digital expanse — impervious to doubt, reigning supreme.

Amid televised allusions, the Zircon-2 hypersonic missile, boasting a purported 2000-kilometer range, assumes corporeal existence within the military inventory. Alas, this apparition remains unseen. An imminent container launcher is set to follow. Progress unfolds in the shape of medium missile ships (SRK), amplifications of MRK housing twin 3S-14 launchers. Regrettably, these ships forfeit air defense and anti-aircraft safeguards; nonetheless, media proclaims their capacity to obliterate aircraft carriers. The Pacific Fleet rejoices in the infusion of Project 22160M patrol ships, distinguished by their elevated speed of 23 knots.

Meanwhile, the United States grapples with a fracturing global trade framework reliant on the dollar. The era of the oil dollar, and akin cycles in global commerce, wanes from its erstwhile supremacy. China’s ascendancy in world trade burgeons. Africa’s transactions evolve into yuan-based transactions. The United States grapples with the waning of its longstanding trillion-dollar negative trade surplus, unleashing cataclysmic repercussions. Remediation is essential, yet how? China’s integration within the Western economic nexus precludes its subjugation without jeopardizing the West itself. A stratagem beckons to reclaim China, ensnaring it anew within the realm of dollar transactions. A quandary persists; Russian support bolsters China, albeit diminished. While Russia’s military alliance stands frayed, the Chinese remain unperturbed, cognizant that Russia’s arsenal holds capacity for action. Alas, the maritime aspect remains deficient.

What if this fragile support were eradicated, pulverized into dust? To vanquish it bears significance. A convocation with the Chairman of the CPC beckons, a proposition irrefutable. Yes, Russia wields nuclear might, buttressed by a sophisticated early warning system. Yet a chink in the armor persists, overlooked in Russia’s fixation on its “continental” and “land” prerogatives.

In March 2030, the Columbia SSBN embarks upon its latest “routine” combat mission. However, this odyssey diverges from convention, bypassing the North Atlantic for a clandestine journey through Gibraltar into the Mediterranean. There, the commander awaits the appointed directive, an atmosphere fraught with unease. Heartland dwellers in Kentucky and Oklahoma loathe this deployment, sensing its aura of desolation. They, the Americans, once deemed themselves champions of virtue. Yet rebellion remains absent, obedience prevails—oaths once sworn command adherence. The Pentagon, seemingly astute, reckons the submarine’s course. No alternative course presents itself.

The greatest adversary lurks beneath the waves. The image reveals the imposing Columbia-class, the latest addition to the US Navy’s fleet of SSBNs.

In the midst of March, the Columbia assumes a strategic stance to the west of the Ionian Islands. At this moment, the destiny of this vessel becomes intertwined with two locations, foreign to the experiences of its entire crew. These two points will forever remain uncharted by them. The initial point is the Engels airbase, nestled in the Saratov region of Russia, serving as the operational hub for the formidable Tu-95, Tu-160, and Tu-160M bombers. The second point is the village of Svetly, lying not too distant from the airbase, housing the 60th missile division of the Strategic Missile Forces. Approximately 2340 kilometers stretch between the “Columbia” and this precise location.

Heading to the 60th missile division and Engels airbase, the strategic significance of ballistic missiles became clear. These projectiles could follow unconventional trajectories, deviating from the typical ballistic curve, which allowed them to fly at lower altitudes. Despite the rocket’s diminished height, the incredible speed and thrust, along with supplementary lift forces, sustained its flight. Yet, this approach came with drawbacks; accuracy suffered, as did range.

Still, even in this flattened trajectory, the missiles could cover over 2000 kilometers in distance. Their speed was the key factor. The time taken to reach their destination was incredibly short, leaving adversaries with minimal reaction time. The Columbia missile salvo, for instance, would blitz the 60th Missile Division and Engels base nearly three times faster than any Russian counter-strike. Early warning systems would prove futile – the Columbia missiles’ flight time was a mere 10 minutes or less. Despite the seemingly impressive firepower of a single “Columbia” volley, it was comparably modest.

Each volley included four missiles, armed with 10 warheads apiece, aiming for Svetly. Launch parameters were reset for another volley of four. The commander’s intent was to intimidate rather than obliterate the Russian forces; the speed of the missiles might not fully cover the missile division.

Yet, this perception shifted when the watch officer, replacing the commander, reported an Ohio-class Wyoming submarine far to the west via acoustics. Suddenly, the bigger picture became evident.

By March 60, the Mediterranean saw the deployment of three American SSBNs targeting the 27th Missile Division and Engels Air Base. An additional four submarines were dispatched to strike the remaining units of the 27th Guards Missile Army from the Barents Sea. The distance from the launch points to Yoshkar-Ola, Teikovo, and Kozelsk was much shorter than from the Mediterranean to Svetly and Engels.

Two more SSBNs were designated for the 42nd division in Svobodny, and three for the Orenburg divisions. Multiple submarines targeted single objectives to compensate for the four-missile salvo. Precision fuses on the W76-2 warheads countered the potential spread along the trajectory. The salvo’s flight time consistently remained under 10 minutes, even less when striking the 27th Missile Army.

Calculations indicated a significant delay (at least five minutes) in the Russian retaliation command.

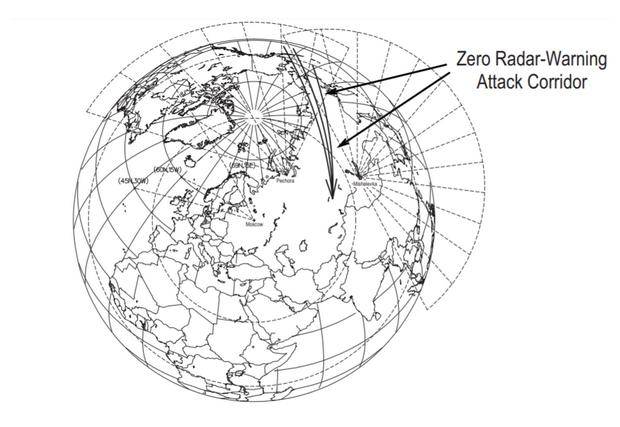

The remaining SSBNs converged in the Pacific Ocean, using a launch corridor that dipped below Russian early warning radar fields, a tactic effective even if launched slightly off course.

Upon striking the formations of the 33rd Guards Missile Army (Irkutsk, Gvardeisky, Solnechny, Sibirskiy), the time elapsed from radar detection to warhead detonation was under five minutes…

This is the familiar corridor, unchanged as always, and it’s projected to remain the same even in 2030. A missile launched following this trajectory would only be detectable by orbiting satellites. If they happen to observe…

The entire situation hinged on whether the Virginias could successfully neutralize two Boreas submarines in time for active duty – one in the northern region and the other in the Sea of Okhotsk. With the notable absence of Russian anti-submarine defenses, this objective appeared relatively uncomplicated.

The next task was to neutralize the Russian submarines harbored in their bases and secure the Ukrainka airbase. The bases were decimated through a series of precision strategic airstrikes, carefully timed to coincide with the submarine assault. Meanwhile, the Ukrainka airbase was allocated “gifts” in the form of ICBMs, as there weren’t enough submarines to cover it adequately. Unlike bombers, which couldn’t execute rapid and unexpected attacks, the ICBMs were the perfect solution. Time was of the essence, and the Russians lacked the capability to respond to a nuclear strike within 15–20 minutes, in contrast to their American counterparts.

Come March 2030, the Columbia submarine, whose commander had already familiarized themselves with the battle orders, surfaced for a communication session.

The previously received directive to launch the attack at the designated time was reaffirmed…

Perhaps we can halt at this point.

Readers, you are now welcomed to embark on a journey of imagination regarding the potential culmination of this tale.

Contemplate what measures could be undertaken to render such a devastating event implausible.

Reflect upon the juncture at which it becomes imperative to initiate the steps essential for averting the occurrence of this calamity. Consider the resources and strategies requisite to thwart this impending catastrophe.

Revisit the inquiry posed by R. Skomorokhov and A. Vorontsov: Does Russia have a need for a formidable naval fleet?

If so, which attributes should this fleet embody?

What capabilities should it possess?

Does the archaic notion of countering a nuclear missile assault from maritime expanses retain its relevance in our context?

Or perhaps it doesn’t? Maybe, in alignment with the authors’ assertions, it’s deemed “untenable to pursue”?

Should we dare to abandon all of this?

Perhaps Russia should continue following the “Vorontsov-style” approach? Is it still worthwhile to invest trillions of rubles in producing a series of naval Tu-160Ms? Will such actions prove effective in the aforementioned scenario?

And what about the coastal fleet?

What about the corvettes?

Maybe it’s time for us to contemplate how we should proceed, rather than chasing after unrealistic dreams? Shouldn’t we make it a priority to fully grasp the intricacies of these matters before expressing our opinions?

Otherwise, tasks that were merely operational and tactical a decade ago could eventually transform into genuine, insurmountable challenges. After all, the politicians of 2030 will be the same individuals who are currently students absorbing the insights of “Military Review.”

However, how can they possibly go astray in their foresight for the future? Could they inadvertently pursue flawed concepts? Might they make logical errors?

And at that point, there won’t be anyone left to debate the necessity or futility of maintaining a fleet.